Contact Admission

International Collaboration

The Gut and the Brain - Guts and Brains

The Gut and the Brain - Ruột Và Não Bộ

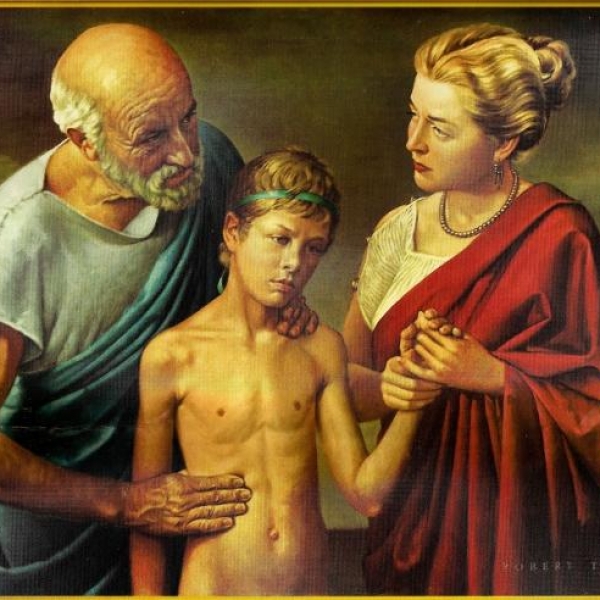

The enteric nervous system that regulates our gut is often called the body’s “second brain.” Although it can’t compose poetry or solve equations, this extensive network uses the same chemicals and cells as the brain to help us digest and to alert the brain when something is amiss. Gut and brain are in constant communication.

The small intestinal nervous system that regulates our intestines is often referred to as the body's "second brain". Although this small intestinal nervous system cannot compose poetry or solve equations, this large network of the small intestinal nervous system uses brain-like chemicals and cells to help us digest. and warns the brain when something goes wrong. The intestines and brain are intimately related.“There is immense crosstalk between these two large nerve centers,” says Braden Kuo, MD, MMSc ’04, co-executive director of the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “This crosstalk affects how we feel and perceive gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and impacts our quality of life.”

"There is a lot of crosstalk between the two," said Dr. Braden Kuo, co-executive director of the Center for Neurological Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, USA and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. "This crosstalk affects our feelings, makes us notice gastrointestinal symptoms, affects our quality of life."

Normally, when we see something tasty, the brain signals the gut to prepare for incoming food. When we feel anxious or stressed, we might experience these as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, or “butterflies.” Messages travel from gut to brain, too. This helps explain why, when we eat something that makes us sick, we instinctively avoid the food and even the place we found it.

Normally, when we notice something delicious, then the brain signals the gut to prepare it for food. When we feel anxious or stressed, we may experience such things as: stomach upset, diarrhea, nausea, or "nervousness". Then the messages also go from the gut to the brain. This helps explain why, when we eat something that makes us sick, we naturally avoid eating it no matter how much we see it.These everyday activities can go awry when gut nerves are damaged or malfunction. The Center for Neurointestinal Health treats patients with life-altering conditions such as chronic constipation, extreme bloating, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Center physician-scientists also contribute to the exciting basic, clinical, and translational research happening across HMS to understand the gut-brain connection.

These day-to-day activities can go awry when the nerves of the gut are damaged or malfunctioning. The Center for Neurological Health treats patients with life-changing conditions such as chronic constipation, vomiting, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS - Irritable Bowel Syndrome). Doctors - The center's scientists also contribute basic research, clinical research and transformation studies at Harvard Medical School to understand the relationship between the gut and the brain.

For example, Kuo and colleagues are measuring brain activity in patients with chronic nausea using functional MRI, which detects blood-flow changes. Their discovery that nausea and pain involve similar nerve centers has prompted new treatment plans for certain patients, potentially improving their quality of life.

Center researchers are also investigating how the trillions of bacteria in the gut (the gut microbiome) interact with the enteric nervous system (a component of the autonomic nervous system) and ultimately with the central nervous system, notes center co-leader Allan M. Goldstein, MD ’93, Marshall K. Bartlett Professor of Surgery at HMS and chief of pediatric surgery at MGH. “Increasing evidence is showing that bacteria in the gut, and the byproducts they produce, affect mood, cognition, and behavior.”

HMS Instructor in Medicine Kyle Staller, MD ’09, MPH ’15, is studying how abnormal body image and eating disorders in adolescents influence the likelihood of developing IBS and other GI problems in adulthood. These patients, he says, typically perceive normal digestion sensations, like the gut’s expansion with food and stool, as abnormal and may seek a doctor’s help for bloating.

Kuo has also co-led a pilot study that found the “relaxation response,” a state of deep rest induced by practices such as meditation and yoga, helped relieve symptoms in some patients with IBS and inflammatory bowel disease.

Tiến sĩ Braden Kuo cũng đồng thời dẫn đầu một nghiên cứu thí điểm cho thấy "phản ứng thư giãn", một trạng thái nghỉ ngơi sâu của các hoạt động như thiền và yoga giúp làm giảm triệu chứng ở một số bệnh nhân bị IBS và bệnh viêm ruột.

With the brain and gut so intertwined, it makes sense for clinicians treating gastrointestinal disorders to include cognitive approaches such as talk therapy, hypnosis, or relaxation response in their recommendations, and for clinicians treating cognitive symptoms to consider what’s happening in the patient’s gut.

Source: http://neuro.hms.harvard.edu

Translation summary: Dr. Nguyen Huu Tung et al

Other news

- How Dangerous Is Nipah Virus? Medical Alert and Urgent Health Recommendations ( 14:13 - 27/01/2026 )

- Predicting Disease from Sleep – A New Breakthrough Study ( 14:01 - 13/01/2026 )

- Medical advances predicted to break through in 2026 ( 13:54 - 12/01/2026 )

- Vietnamese medical miracles in 2025 – inspiration for medical students ( 07:54 - 07/01/2026 )

- Updating the SOFA-2 Score: A New Standard in the Assessment of Multiple Organ Failure After Three Decades ( 10:40 - 31/12/2025 )

- Home AEDs: High Life-Saving Effectiveness, but Not Cost-Effective at Current Prices ( 14:12 - 18/12/2025 )

- Artificial Intelligence and Pediatric Care ( 08:27 - 16/12/2025 )

- Applying Clinical Licensing Principles to Artificial Intelligence ( 09:36 - 08/12/2025 )

- U.S. Approves Targeted Lung Cancer Therapy Datroway ( 08:43 - 25/06/2025 )

- Therapeutic potential and mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as bioactive materials in tendon–bone healing ( 08:38 - 23/11/2023 )