Contact Admission

International Collaboration

Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography – A Mysterious Case of ST Elevation

A patient in their 70s presented to the emergency department with symptoms of palpitations, fatigue, and shortness of breath. The patient had been diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung with metastasis to the right hilar lymph nodes and the gallbladder wall one month prior to admission. Twenty days earlier, the patient had received the first cycle of sintilimab (a programmed cell death protein 1 [PD-1] immune checkpoint inhibitor, ICI) in combination with vinorelbine. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed upon admission to the emergency department.

Yi-Shuo Liu, BS; Samuel Chin Wei Tan, BS; Yun-Tao Zhao, MD

Dr. Nguyễn Lê Rân – translated and summarized

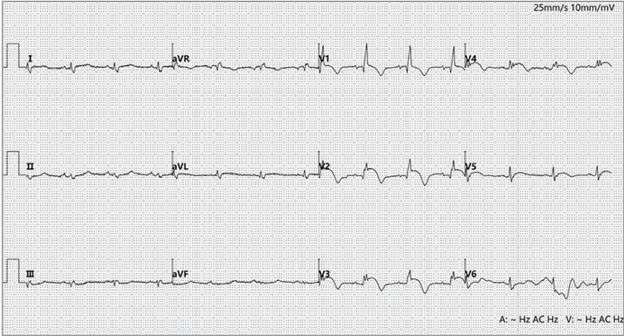

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram at Emergency Department admission

Electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation with T-wave inversion in leads V1 to V5, suggesting acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Coronary CT angiography (CTA) performed 1 year earlier demonstrated a normal left anterior descending artery, and the patient had no history of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, or other cardiovascular risk factors. Further tests revealed persistently elevated serum high-sensitivity troponin I (hsTnI) at 2038.7 ng/L (normal, <11.6 ng/L; to convert to μg/L, multiply by 0.001) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) at 1968 pg/mL (normal, <100 pg/mL; to convert to ng/L, multiply by 1), indicating myocardial injury. Transthoracic echocardiography showed significantly reduced left ventricular systolic function, with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 40%, without left ventricular hypertrophy or regional wall motion abnormalities.

Question: What additional findings can be detected on the electrocardiogram? What potential causes could explain these findings?

Interpretation

The tracing shows sinus rhythm at a rate of 80 beats/min. In addition to ST elevation, the ECG demonstrates low voltage in the limb leads (QRS amplitude <0.5 mV) and right bundle branch delay with q waves in leads V1 and V2 (QRS duration: 124 ms). Although precordial ST elevation suggests acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), the absence of reciprocal ST depression in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) is not consistent with a typical STEMI. The diffuse low-voltage QRS complexes are consistent with myocardial edema. The combination of electrical abnormalities and markedly elevated hsTnI levels suggests myocarditis. This is further supported by echocardiographic findings of reduced left ventricular systolic function, possibly resulting from underlying inflammatory injury. Given the patient’s recent sintilimab therapy for lung cancer and prior normal CTA, the diagnosis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated myocarditis (ICI-M) was strongly considered.

Clinical Course

The patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroids (intravenous methylprednisolone) for 3 days within 24 hours of admission. However, the condition continued to deteriorate, ultimately resulting in death from refractory heart failure.

Discussion

ICI-M is a potentially life-threatening complication of ICI therapy, with a wide spectrum of clinical outcomes ranging from asymptomatic cardiac biomarker elevation and ECG abnormalities to severe cardiac dysfunction and multiorgan failure. Moreover, distinguishing it from other life-threatening conditions such as STEMI is often challenging. In this patient, concurrent precordial ST elevation initially raised concern for anterior STEMI. However, the absence of reciprocal ST depression in the inferior leads ruled out a typical ischemic pattern. In STEMI, ST elevation usually corresponds to coronary territories and is often accompanied by reciprocal changes in opposing leads, a feature not seen here. ICI-M often manifests with non-territorial ST elevation, involving multiple regions such as both anterolateral and inferior leads, without reciprocal depression. This pattern reflects diffuse myocardial inflammation rather than ischemia. Additionally, low-voltage QRS complexes suggest impaired electrical conduction secondary to myocardial edema, while right bundle branch delay further points to inflammatory involvement of the conduction system—both findings described in ICI-M. Such ECG abnormalities, when considered alongside persistently elevated hsTnI levels and echocardiographic evidence of global LV dysfunction, indicate diffuse myocarditis affecting cellular integrity and conduction. Taken together with recent CT results and characteristic ECG changes, the diagnosis of ICI-M was strongly supported.

ICI-M typically presents early, often within the first few weeks after initiation of therapy. Approximately 62%–96% of patients with ICI-M exhibit ECG abnormalities, including repolarization changes, conduction defects, and ventricular arrhythmias. Elevated cardiac biomarkers, particularly hsTnI, are present in over 90% of cases and serve as sensitive predictors of adverse cardiovascular events. Pathophysiologically, ICI-M is thought to result from T-cell–mediated immune activation leading to diffuse myocardial inflammation. These changes disrupt normal cardiac electrophysiology through inflammatory depolarization and altered conduction, producing non-territorial ST-segment shifts and conduction abnormalities. Echocardiographic findings vary; while some patients maintain preserved LVEF, others exhibit reduced LVEF, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of myocardial injury. Endomyocardial biopsy remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis but is typically reserved for patients with inconclusive noninvasive testing. In this case, markedly elevated hsTnI, ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography, absence of coronary artery disease on CTA, and recent sintilimab therapy were consistent with ICI-M.

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guidelines, immediate and permanent discontinuation of ICI therapy is strongly recommended upon diagnosis of myocarditis. Early initiation of high-dose corticosteroids is critical to reduce myocardial injury, supported by retrospective studies showing a 40% reduction in mortality when steroids are administered within 24 hours of symptom onset. For patients with persistent clinical or biomarker abnormalities (e.g., sustained troponin elevation or hemodynamic instability) after 72 hours of glucocorticoid therapy, escalation to biologic agents such as antithymocyte globulin or abatacept should be guided by a multidisciplinary cardio-oncology team.

Despite early initiation of high-dose corticosteroids, treatment was unsuccessful in this case, underscoring the severity of ICI-M and the need for aggressive, timely intervention. Given the potentially life-threatening nature of ICI-M, it is crucial for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients undergoing ICI therapy who present with ECG changes. Early recognition and intervention are essential to minimize the risk of serious complications.

Key Points

-

ICIs can cause severe adverse reactions such as myocarditis. Clinicians should maintain high suspicion for myocarditis in ICI-treated patients presenting with signs of myocardial injury and ECG changes.

-

In ICI-M, the ECG may show ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion, or conduction abnormalities after ICI therapy, highlighting the need for careful differential diagnosis.

-

Early diagnosis and intervention are critical for managing ICI-M, as standard treatments such as corticosteroids may not always be effective, requiring timely and aggressive therapy.

Other Case Report

- New Secrets About Psoriatic Arthritis: Is Combination Therapy as Safe as You Think? ( 14:33 - 06/09/2025 )

- Mitrofanoff procedure: more 40 years later. ( 07:36 - 28/03/2025 )

- Telehealth vs In-Person Early Palliative Care for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer ( 09:26 - 12/10/2024 )

- ST-Segment Elevation in a Woman With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest ( 08:35 - 24/09/2024 )

- Scrotal Rash for Months ( 11:07 - 31/05/2024 )

- Lower Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage ( 16:15 - 16/05/2024 )

- Can Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Be Improved in the 21st Century? ( 15:57 - 16/05/2024 )

- Approach to Obesity Treatment in Primary Care ( 14:04 - 20/03/2024 )

- Fever, Rash, and Shortness of Breath in a 69-Year-Old ( 09:20 - 04/03/2024 )