Contact Admission

International Collaboration

Overdiagnosis: When the Boundaries of Disease Become Blurred

Changing Definitions of Disease and Diagnostic Criteria The evolving definitions of diseases and diagnostic standards are having a profound impact on healthcare, often leading to overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis refers to labeling individuals with diseases that would not have caused symptoms or shortened lifespan, usually due to lowered diagnostic thresholds or the detection of minor abnormalities. This results in consequences such as resource waste and healthy individuals perceiving themselves as patients, which threatens the sustainable development of healthcare systems.

Changes in Disease Definitions and Diagnostic Standards

Currently, there remains significant disagreement over what constitutes a disease. The naturalistic perspective views disease as an objectively harmful deviation from normal bodily functions. In contrast, the social constructionist view emphasizes the role of social norms and economic interests in shaping the concept of disease. Examples such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and post-COVID syndrome illustrate the challenges of defining disease when their biological foundations remain unclear.

In this context, diagnostic criteria may change over time, sometimes resulting in the emergence of new disease entities (e.g., COVID-19 or early-stage cancers due to advanced diagnostics). Criteria for known diseases have also been revised, as seen with diabetes since the 1960s. Psychiatry has witnessed similar shifts, with each revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) introducing new conditions and modifying criteria for existing ones. Guideline-setting committees often tend to broaden definitions, increasing the number of individuals diagnosed with a condition.

Differences in Perceptions of Illness

Interestingly, an individual's perception of their own health condition may differ from a physician's assessment. Some people feel healthy despite having serious illness, while others perceive themselves as ill despite no identified abnormalities. A large survey revealed significant differences in perceptions of disease among the general public, physicians, nurses, and members of parliament. For example, among 60 conditions surveyed, only 20% (such as diabetes and pneumonia) were considered diseases by at least 80% of participants, while 8% (such as aging and homosexuality) were considered not to be diseases. For many other conditions—such as erectile dysfunction or menopause—there remains considerable disagreement

Consequences of Lowering Diagnostic Thresholds: Overdiagnosis

Changing diagnostic thresholds has a clear impact on disease prevalence. The table below illustrates a sharp increase in prevalence rates when cut-off thresholds are lowered for common clinical indicators:

| Analytical Index | Cutoff Threshold (mg/dL or mm Hg) |

Prevalence Rate (%) |

|

Total Cholesterol |

180 | 54 |

| 240 | 10 | |

|

Fasting Blood Glucose |

100 | 61 |

| 126 | 12 | |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 110 | 75 |

| 140 | 14 |

The expansion of diagnostic criteria—for example, for gestational diabetes—has led to a doubling of the disease prevalence without improving health outcomes for either mothers or newborns. In psychiatry, broadening diagnostic criteria also risks pathologizing normal behavior, such as labeling shyness as social anxiety disorder or everyday restlessness as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Under the influence of commercialism, direct-to-consumer advertising, and a desire for perfect health—fueled by a “more is better” culture—modern medicine has developed a tendency toward overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Overdiagnosis refers to labeling individuals with diseases that would never cause symptoms or shorten life expectancy. A clear example is cancer screening programs that detect slow-growing tumors that are not harmful, leading to unnecessary monitoring and treatment. The heightened sensitivity of modern imaging techniques also increases the likelihood of detecting incidental abnormalities in joints, discs, and blood vessels—findings that are often best left alone. Advances in artificial intelligence and genetic testing may also contribute to this trend.

Consequences of Overdiagnosis

Recognizing more conditions as diseases may help improve access to treatment but also raises the risk of people with normal variations of life perceiving themselves as ill. Being labeled with a disease can negatively impact employment prospects, especially in contexts where diagnoses affect insurance or job opportunities. Allocating medical resources to individuals who are essentially healthy also leads to opportunity costs, including delays in care for those who need it most. This is a global issue, as expanded screening, advanced imaging technologies, and misaligned financial incentives all contribute to overdiagnosis in both high-income and low- to middle-income countries.

Balance and Sustainability

To address these issues, clinicians must remain alert to commercial and societal influences. They should make decisions through shared decision-making with patients, balancing patient values with evidence-based diagnostic thresholds. Trusted resources such as the “Less is More” series from JAMA Internal Medicine, the international Choosing Wisely campaign, and the “Too Much Medicine” initiative from The BMJ can offer valuable guidance.

Distinguishing whether a patient’s symptoms stem from a treatable condition or are merely part of normal human variation is crucial to ensure that diagnosis genuinely improves health outcomes and quality of life. The global challenge of defining disease highlights the need to balance expanding access to care with avoiding medicalization and inefficient use of resources.

This article was adapted and translated by Dr. Nguyễn Lê Rân.

For more details, please refer to the original publication in JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association).

This article was adapted and translated by Dr. Nguyễn Lê Rân.

For more details, please refer to the original publication in JAMA

Other research

- Continuous Medical Knowledge Tied to Better Clinical Outcomes in Internal Medicine ( 10:56 - 19/06/2025 )

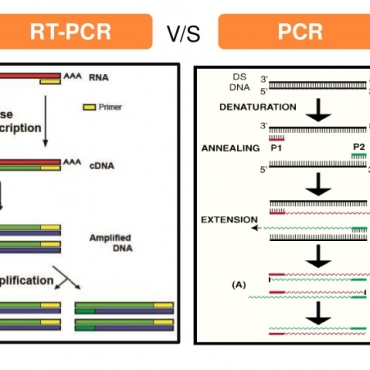

- Rapid and sensitive diagnostic procedure for multiple detection of pandemic Coronaviridae family members SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV: a translational research and cooperation between the Phan Chau Trinh University in Vietnam and Universit ( 15:42 - 29/06/2020 )

- PCTU studies at ISSAR 2019 international conference - Gyeongju, Korea ( 16:17 - 04/11/2019 )

- Melioidosis in Vietnam: Recently Improved Recognition but still an Uncertain Disease Burden after Almost a Century of Reporting ( 13:29 - 27/04/2018 )

- Microbiological agents causing community pneumonia require hospitalization ( 11:20 - 03/02/2018 )

- The in-vitro activity of sitafloxacin against the most common bacterial pathogens isolated from the clinical samples ( 11:10 - 03/02/2018 )

- Evaluate the role of the microbiological molecular biology tests in the early detection of pathogens causing lower respiratory infections ( 10:52 - 03/02/2018 )

- Production and evaluation of the kit using magnetic silica coated nano-iron beads to extract the nucleic acid from different samples ( 10:16 - 03/02/2018 )

- Challenges in selecting antibiotics treatment for H. Pylori in Vietnam ( 09:12 - 03/02/2018 )

- The resistance of the gram-negative rods isolated from clinical cases in Vietnam to doripenem ( 08:46 - 03/02/2018 )