Contact Admission

International Collaboration

Effect of Helmet Noninvasive Ventilation vs High-Flow Nasal Oxygen on Days Free of Respiratory Support in Patients With COVID-19 and Moderate to Severe Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure

Effect of Helmet Noninvasive Ventilation vs High-Flow Nasal Oxygen on Days Free of Respiratory Support in Patients With COVID-19 and Moderate to Severe Hypoxemic Respiratory FailureThe HENIVOT Randomized Clinical Trial

Domenico Luca Grieco, MD1,2; Luca S. Menga, MD1,2; Melania Cesarano, MD1,2; et alTommaso Rosà, MD2; Savino Spadaro, MD, PhD3; Maria Maddalena Bitondo, MD4; Jonathan Montomoli, MD, PhD4; Giulia Falò, MD3; Tommaso Tonetti, MD5; Salvatore L. Cutuli, MD1,2; Gabriele Pintaudi, MD1,2; Eloisa S. Tanzarella, MD1,2; Edoardo Piervincenzi, MD1,2; Filippo Bongiovanni, MD1,2; Antonio M. Dell’Anna, MD1,2; Luca Delle Cese, MD1,2; Cecilia Berardi, MD1,2; Simone Carelli, MD1,2; Maria Grazia Bocci, MD1,2; Luca Montini, MD1,2; Giuseppe Bello, MD1,2; Daniele Natalini, MD1,2; Gennaro De Pascale, MD1,2; Matteo Velardo, PhD6; Carlo Alberto Volta, MD3; V. Marco Ranieri, MD5; Giorgio Conti, MD1,2; Salvatore Maurizio Maggiore, MD, PhD7,8; Massimo Antonelli, MD1,2; for the COVID-ICU Gemelli Study Group

JAMA. 2021;325(17):1731-1743. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4682

Key Points

Question Among patients admitted to the intensive care unit with COVID-19–induced moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, does early continuous treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation increase the number of days free of respiratory support at 28 days as compared with high-flow nasal oxygen?

Findings In this randomized trial that included 109 patients, the median number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days was 20 days in the group that received helmet noninvasive ventilation and 18 days in the group that received high-flow nasal oxygen, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning Among critically ill patients with moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19, helmet noninvasive ventilation, compared with high-flow nasal oxygen, resulted in no significant difference in the number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days.

Abstract

Importance High-flow nasal oxygen is recommended as initial treatment for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and is widely applied in patients with COVID-19.

Objective To assess whether helmet noninvasive ventilation can increase the days free of respiratory support in patients with COVID-19 compared with high-flow nasal oxygen alone.

Design, Setting, and Participants Multicenter randomized clinical trial in 4 intensive care units (ICUs) in Italy between October and December 2020, end of follow-up February 11, 2021, including 109 patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure (ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ≤200).

Interventions Participants were randomly assigned to receive continuous treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation (positive end-expiratory pressure, 10-12 cm H2O; pressure support, 10-12 cm H2O) for at least 48 hours eventually followed by high-flow nasal oxygen (n = 54) or high-flow oxygen alone (60 L/min) (n = 55).

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome was the number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days after enrollment. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who required endotracheal intubation within 28 days from study enrollment, the number of days free of invasive mechanical ventilation at day 28, the number of days free of invasive mechanical ventilation at day 60, in-ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, 60-day mortality, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay.

Results Among 110 patients who were randomized, 109 (99%) completed the trial (median age, 65 years [interquartile range {IQR}, 55-70]; 21 women [19%]). The median days free of respiratory support within 28 days after randomization were 20 (IQR, 0-25) in the helmet group and 18 (IQR, 0-22) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group, a difference that was not statistically significant (mean difference, 2 days [95% CI, −2 to 6]; P = .26). Of 9 prespecified secondary outcomes reported, 7 showed no significant difference. The rate of endotracheal intubation was significantly lower in the helmet group than in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (30% vs 51%; difference, −21% [95% CI, −38% to −3%]; P = .03). The median number of days free of invasive mechanical ventilation within 28 days was significantly higher in the helmet group than in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (28 [IQR, 13-28] vs 25 [IQR 4-28]; mean difference, 3 days [95% CI, 0-7]; P = .04). The rate of in-hospital mortality was 24% in the helmet group and 25% in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (absolute difference, −1% [95% CI, −17% to 15%]; P > .99).

Conclusions and Relevance Among patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemia, treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation, compared with high-flow nasal oxygen, resulted in no significant difference in the number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days. Further research is warranted to determine effects on other outcomes, including the need for endotracheal intubation.

Introduction

The role of noninvasive respiratory support in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure is debated.1 Noninvasive ventilation may help avoid endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation; however, the rate of treatment failure can be as high as 60%, and patients exposed to delayed intubation experience worse clinical outcome.2-4

The uncertainty about the initial management of hypoxemic respiratory failure has been emphasized by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hypoxemic respiratory failure is the most frequent life-threatening complication of COVID-19. The optimal initial respiratory support for these patients is controversial, and different approaches have been applied with variable success rates.5-7 Because high-flow nasal oxygen is simple to use and has clinical and physiological effects, it is recommended as the first-line intervention for respiratory support in patients with hypoxemia8 and is widely applied in patients with COVID-19.7,9

Helmet noninvasive ventilation has recently been advocated as an alternative for management of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure,10-12 but its use is limited by the lack of evidence regarding its efficacy. Putative benefits of this technique include the possibility to deliver longer-term treatments with higher levels of positive end-expiratory pressure, which may be crucial to improve hypoxemia and prevent progression of lung injury during spontaneous breathing.13,14 Helmet noninvasive ventilation may confer physiological advantages compared with high-flow oxygen,15 but whether these translate into a clinical benefit remains to be established.

This open-label, multicenter, randomized clinical trial was conducted in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19 to assess whether early treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation in comparison with high-flow nasal oxygen increased the days free of respiratory support within 28 days after randomization.

Methods

The Helmet Noninvasive Ventilation Versus High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure (HENIVOT) Trial was an investigator-initiated, 2-group, open-label, multicenter, randomized clinical trial conducted in 4 intensive care units in Italy between October 13, 2020, and December 13, 2020; 60-day follow up was completed by February 11, 2021. The study was supported by the acute respiratory failure study group of the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care Medicine and was approved by the ethics committee of all participating centers (coordinating center: Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS; ethics committee approval ID3503). All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2, respectively.

Participants

All consecutive adult patients admitted in the intensive care units due to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure were screened for enrollment. The study was originally designed for including patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure from all causes, but, due to the surge of the ongoing pandemic, only included patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

Eligibility inclusion criteria were assessed within the first 24 hours from intensive care unit admission, while patients were receiving oxygen through a Venturi mask, with nominal fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) ranging between 24% and 60% as set by the attending physician.

Patients were enrolled if all of the following inclusion criteria were met: ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (Pao2/Fio2) equal to or below 200, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (Paco2) equal to or lower than 45 mm Hg, absence of history of chronic respiratory failure or moderate to severe cardiac insufficiency (New York Heart Association class >II or left ventricular ejection fraction <50%), confirmed molecular diagnosis of COVID-19, and written informed consent. Acute exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease and kidney failure were the main exclusion criteria (full list of exclusion criteria is provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 3). Patients who had already received noninvasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen for more than 12 hours at the time of screening were excluded.

Randomization

Enrolled patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either helmet noninvasive ventilation or high-flow nasal oxygen. A computer-generated randomization scheme with randomly selected block sizes ranging from 3 to 9 managed by a centralized web-based system was used to allocate participants to each group.

Study Treatments

Patients had to receive the allocated treatment within 1 hour from validation of enrollment criteria. In both groups, the allocated treatment was continued until the patient required endotracheal intubation or (in case of no intubation) up to intensive care unit discharge.

In the high-flow group, patients received nasal high-flow oxygen (Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, New Zealand) continuously for at least 48 hours. Gas flow was initially set at 60 L/min and eventually decreased in case of intolerance, Fio2 titrated to obtain peripheral oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry (Spo2) between 92% and 98%, and humidification chamber was set at 37 °C or 34 °C according to the patient’s comfort.16 After 48 hours, weaning from high-flow oxygen was allowed if the Fio2 was equal to or lower than 40% and the respiratory rate was equal to or lower than 25 breaths/min. Oxygen flow was lowered to 10 L/min, keeping Fio2 unchanged. Weaning from high-flow nasal oxygen was considered successful if the Spo2 remained between 92% and 98% and the respiratory rate was lower than 25 breaths/min with this setting. In this case, high-flow oxygen was replaced by Venturi mask or nasal cannula: oxygen flow or Fio2 were set to obtain the same Spo2 target. High-flow nasal oxygen could be resumed at any time if the patient experienced respiratory distress and hypoxemia (Spo2 <92%). Use of noninvasive ventilation was not permitted in the high-flow group.

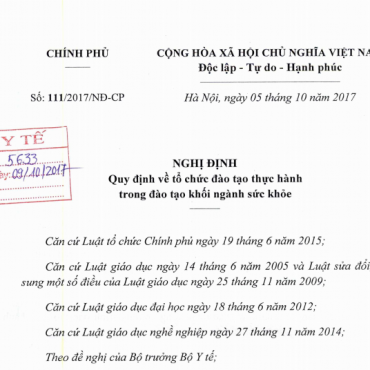

Patients in the noninvasive ventilation group received 48-hour continuous noninvasive ventilation through the helmet interface (Dimar, Italy, or Starmed-Intersurgical, UK). Helmet size was chosen according to neck circumference. Noninvasive ventilation was delivered by a compressed gas-based ventilator connected to the helmet through a bi-tube circuit, as displayed in Figure 1. The ventilator was set in pressure support mode, with the following settings10,15: initial pressure support between 10 and 12 cm H2O, eventually increased to ensure a peak inspiratory flow of 100 L/min; positive end-expiratory pressure between 10 and 12 cm H2O; and Fio2 titrated to obtain Spo2 between 92% and 98%. Any modification in ventilator settings and interface setup to optimize comfort and patient-ventilator interaction was allowed at the discretion of the attending physicians, but positive end-expiratory pressure had to be kept equal to or greater than 10 cm H2O. After 48 hours, interruption of noninvasive ventilation was attempted when Fio2 was equal to or lower than 40% and respiratory rate was equal to or lower than 25 breaths/min. Weaning was performed by reducing positive end-expiratory pressure and pressure support to 8 cm H2O. If the patient maintained Spo2 equal to or greater than 92% and respiratory rate equal to or lower than 25 breaths/min for 30 minutes, noninvasive ventilation was interrupted. After interruption of noninvasive ventilation, patients underwent continuous Venturi mask or high-flow nasal oxygen, according to the choice of the attending physician: oxygen flow and Fio2 were set to obtain the same Spo2 target. Helmet noninvasive ventilation could be resumed at any time if the respiratory rate was greater than 25 breaths/min and/or Spo2 was lower than 92%.

Standard Care

In both groups, standard care was delivered according to the clinical practice of each institution.

Intravenous sedation was allowed according to the physician’s preference, but the concurrent use of sedative drugs and opioids was discouraged.17 Use of prone positioning during the treatment was left to the choice of treating physicians.18 Use of face mask noninvasive ventilation before endotracheal intubation was only allowed in case of respiratory acidosis (ie, Paco2 >45 mm Hg, with pH level <7.35).

Treatment Failure

Treatment failure was defined as the need for endotracheal intubation. The decision to intubate was based on predefined criteria10,19,20 indicating persisting or worsening respiratory failure, which included at least 2 of the following: worsening or unchanged unbearable dyspnea; lack of improvement in oxygenation and/or Spo2 below 90% for more than 5 minutes without technical dysfunction; lack of improvement of signs of respiratory-muscle fatigue; development of unmanageable tracheal secretions; respiratory acidosis with a pH level below 7.30 despite face mask noninvasive ventilation; and intolerance to the used device. Patients were also intubated if they developed hemodynamic instability (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg, mean blood pressure <65 mm Hg, and/or requirement for high-dosage vasopressors with hyperlactatemia) or deterioration of neurologic status with a Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 12 points or seizures.

Because the final decision on intubation was left to the physician in charge who could not be blinded to the study group, 2 independent experts blindly reviewed a posteriori the records and verified whether the decision to intubate was unbiased and in compliance with the required criteria. In case of disagreement between experts, a third physician established whether the criteria had been met.

After intubation, adherence to acute respiratory distress syndrome guidelines was encouraged21: setting of tidal volume at 6 mL/kg of predicted body weight and 48 hours of paralysis and prone position were suggested for patients with Pao2/Fio2 ratio lower than 150. Following current guidelines, daily assessment for readiness for extubation was recommended and use of high-flow nasal oxygen after extubation was encouraged.8,22,23 The decision to perform tracheostomy to enhance the weaning process was left to the attending physicians.

Measurements

Patient demographic characterisitcs were collected at study entry. Ventilator settings, arterial blood gases, dyspnea, and device-related discomfort were recorded at study entry and 1 hour, 6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours after randomization, and then on a daily basis up to 28 days or intensive care unit discharge. Dyspnea and device-related discomfort were assessed with visual analog scales adapted for critically ill patients, ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the worst symptom.15 The need for endotracheal intubation and all-cause mortality at 28 and 60 days after randomization, at intensive care unit discharge, and at hospital discharge were recorded. All data were recorded on a dedicated web-based platform.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the number of days free of respiratory support (including high-flow nasal oxygen, noninvasive and invasive ventilation) within 28 days after enrollment.

Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who required endotracheal intubation within 28 days from study enrollment, the number of days free of invasive mechanical ventilation at days 28 and 60, in–intensive care unit mortality, in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, 60-day mortality, intensive care unit length of stay, and hospital length of stay. Ninety-day mortality and quality of life after 6 and 12 months were among the prespecified secondary outcomes, but results are not reported. Safety end points included the causes of endotracheal intubation, the time between randomization and endotracheal intubation, and any event yielding the need for emergency intubation.

Exploratory outcomes included Pao2/Fio2 ratio, Paco2, respiratory rate, device-related discomfort (assessed by visual analog scale), and dyspnea (assessed by visual analog scale) over the initial 48 hours of treatment. Rates of intensive care unit–acquired infections, tracheostomy, acute kidney injury requiring kidney replacement therapy, barotrauma, upper limb vessel thrombosis, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and liver failure were also assessed.

Power Analysis

Systematic data about the number of days free of respiratory support in patients affected by hypoxemic respiratory failure with Pao2/Fio2 lower than 200 and treated solely with high-flow nasal oxygen are lacking. Data from a single-center exploratory report indicated that the mean (SD) 28-day respiratory support–free days of patients receiving first-line treatment with high-flow nasal oxygen was 11.6 (5) days.24 We hypothesized that this parameter would be 25% higher in patients receiving helmet noninvasive ventilation (14.5 days). Based on consensus among 3 investigators (D.L.G., S.M.M., M.A.), this was deemed to potentially represent a clinically relevant effect of the intervention. Assuming a normal distribution of the primary outcome, we calculated that the enrollment of 50 patients per group would provide 80% power to detect a 25% increase in the number of ventilator support–free days on a 28-day basis in the helmet group, with an α level of .05. The attrition rate was expected to be less than 10% and likely due to protocol violations, absence of objective criteria to define the need for endotracheal intubation, crossover, and dropouts. We planned to enroll a total of 110 patients.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as number of events (percentage) or median (interquartile rage). Data were tabulated descriptively by study group and analyzed for all randomized patients in the primary analysis. A prespecified secondary analysis was conducted after exclusion of patients who showed major protocol deviations, defined as crossover between treatment protocols and the case of assigned treatment not provided due to any reason.

Ordinal qualitative variables or nonnormal quantitative variables were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Normally distributed quantitative variables were assessed with the t test. In particular, intergroup difference in the primary outcome measure was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, after the nonnormal distribution of this variable was determined with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons between groups regarding qualitative variables were performed with the Fisher exact test. Intergroup differences in quantitative variables distribution in the initial 48 hours of treatment were assessed with analysis of variance.

Data on the endotracheal intubation were assessed both in terms of crude reintubation rate and after exclusion of patients for whom the decision to intubate was not deemed adherent to the criteria of the protocol by the external experts. Kaplan-Meier curves are displayed for results concerning intubation rate; the graphical representation showed no evidence against the assumption of proportionality. Post hoc analyses were conducted to establish the potential effect of covariates on the primary outcome measure and on the occurrence of endotracheal intubation. For this purpose, a mixed-effect modeling including site and time of enrollment as random effects and significant covariates (study group and all demographic variables showing association with the event endotracheal intubation with a P ≤ .05 at the bivariable analysis) as fixed effects was performed.

There were no missing data for the primary, secondary, and safety end points. There were missing data in the exploratory end points due to the occurrence of endotracheal intubation during the initial 48 hours. Because data were not missing at random but mainly due to the consequence of treatment effect, we did not perform multiple imputation and excluded missing values from analysis.

All results with 2-sided P ≤ .05 are considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings from analyses on secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Statistical analysis was performed with R Project for Statistical Computing (version 4.0.4).

Results

Between October 13 and December 13, 2020, a total of 182 patients were admitted to the 4 participating intensive care units due to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure; among 149 spontaneously breathing patients, 110 were eligible for inclusion in the study and underwent randomization (Figure 2). Fifty-five patients were assigned to each group. After secondary exclusion of 1 patient who had a newly diagnosed end-stage pulmonary fibrosis with do-not-intubate order, 109 patients were included in the follow-up and in the primary analysis.

Two patients showed major protocol violations: 1 patient received noninvasive ventilation despite being assigned to the high-flow nasal oxygen group, and 1 patient did not receive helmet noninvasive ventilation because of ventilator unavailability; 107 patients were included in the prespecified secondary analysis on patients who did not show protocol violations.

The characteristics of the patients at enrollment are displayed in Table 1. Results of the primary analysis on all randomized patients are reported in Table 2. Results of the prespecified secondary analysis are reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 3.

Characteristics at Inclusion

All randomized patients had confirmed molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 (positive real-time polymerase chain reaction for viral RNA performed on an upper or lower respiratory tract specimen). While receiving oxygen therapy with a Venturi mask before randomization, their median Pao2/Fio2 ratio was 102 (interquartile range [IQR], 82-125) and the median respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min (IQR, 24-32).

Treatments

In the helmet group, noninvasive ventilation was delivered continuously in the first 48 hours or until intubation in 49 patients (91%); 2 patients (4%) did not undergo continuous treatments but received helmet noninvasive ventilation for at least 16 hours in each of the first 2 days. Two patients (4%) could not tolerate the interface and interrupted noninvasive ventilation without receiving 16 hours per day of treatment. One patient did not receive noninvasive ventilation despite assignment to this group.

Helmet noninvasive ventilation was delivered with a median positive end-expiratory pressure of 12 cm H2O (IQR, 10-12) and a median pressure support of 10 cm H2O (IQR, 10-12) (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

In the high-flow nasal oxygen group, treatment was delivered continuously for 48 hours or until intubation in 48 patients (87%). Six patients improved and were successfully weaned to the Venturi mask before 48 hours, none of whom required endotracheal intubation afterwards. One patient stopped receiving high-flow nasal oxygen and received noninvasive ventilation. A median flow of 60 L/min (IQR, 60-60) was initially applied to all patients (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

Continuous infusion of sedative/analgesic drugs was administered to 20 patients (37%) in the helmet group and in 10 patients (18%) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group. Over the initial 48 hours of treatment, the mean (SD) Fio2 used in the helmet and high-flow nasal oxygen groups were 0.54 (0.12) and 0.58 (0.9), respectively. As per clinical decision, 32 patients (60%) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group vs 0 in the helmet group underwent prone position.

Primary Outcome

The median days free of respiratory support within 28 days after randomization were 20 (IQR, 0-25) in the helmet group and 18 (IQR, 0-22) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .26). The mean (SD) days free of respiratory support at 28 days in the groups were 15 (11) and 13 (11), respectively (mean difference, 2 days [95% CI, −2 to 6]).

Secondary Outcomes

Of 9 prespecified secondary end points, 7 showed no significant difference between groups.

Forty-four patients required endotracheal intubation within 28 days after randomization. The decision to intubate the patients was deemed adherent to the predefined criteria of the protocol by the independent experts for all but 1 patient.

The rate of endotracheal intubation was significantly lower in the helmet group than in the high-flow nasal oxygen group: 30% vs 51%, with an absolute risk reduction of 21% (95% CI, 3%-38%) and an unadjusted odds ratio of 0.41 (95% CI, 0.18-0.89; P = .03) (Table 2 and Figure 3).

The median numbers of days free of invasive ventilation within 28 days from enrollment were 28 (IQR, 13-28) in the helmet group vs 25 (IQR, 4-28) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group, a difference that was statistically significant (mean difference, 3 days [95% CI, 0-7]; P = .04).

Safety End Points

The median time between enrollment and intubation was 29 hours (IQR, 8-71) in the helmet group and 21 hours in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (IQR, 4-65), a difference that was not statistically significant (mean difference, −7 hours [95% CI, −60 to 46]; P = .45) (Table 2).

No patient required emergency intubation in the study cohort.

Among the prespecified causes that led to endotracheal intubation, patients in the helmet group showed significantly lower incidence of hypoxemia (28% vs 49%; absolute difference, −21% [95% CI, −38% to −3%]; odds ratio, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.18-0.88]; P = .03), worsening or unbearable dyspnea (17% vs 45%; absolute difference, −29% [95% CI, −44% to −11%]; odds ratio, 0.24 [95% CI, 0.10-0.59]; P = .002), and signs of respiratory muscle fatigue (24% vs 44%; absolute difference, −20% [95% CI, −36% to −2%]; odds ratio, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.18-0.93]; P = .04).

Exploratory End Points

Over the initial 48 hours of treatment, oxygenation and dyspnea were improved in the helmet group, while device-related discomfort and Paco2 were lower in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (Figure 4; eTable 2 in Supplement 3).

The mean (SD) Pao2/Fio2 in the helmet group was 188 (73) vs 138 (46) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (mean difference, 59 [95% CI, 39-61]; P < .001), dyspnea rated on a visual analog scale was 1.9 (2) in the helmet group vs 2.5 (2.2) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (mean difference, −0.5 [95% CI, −1 to −0.2]; P = .003), discomfort rated on a visual analog scale was 3.7 (3.1) in the helmet group vs 1.8 (2.4) in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (mean difference, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.4-2.5]; P < .001), and Paco2 was 36 (5) mm Hg in the helmet group vs 35 (4) mm Hg in the high-flow nasal oxygen group (mean difference, 1 [95% CI, 0-2]; P < .001).

There were no statistically significant differences in any of the other analyzed exploratory outcomes (Table 2).

Secondary and Post Hoc Analyses

In the prespecified secondary analysis that excluded 2 patients with major protocol deviations, the primary outcome of number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days after randomization was not statistically different between the study groups (mean difference, 2 days [95% CI, −2 to 6]; P = .25).

After the exclusion of the single patient for whom intubation was deemed not adherent to the prespecified criteria of the protocol by the external expert review, the difference in the rate of endotracheal intubation remained significant (28% vs 51%; absolute risk reduction, 23% [95% CI, 5%-39%]; unadjusted odds ratio, 0.37 [95% CI, 0.17-0.82]; P = .02).

In a post hoc multivariable analysis with adjustment for site, time of randomization, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, and Pao2/Fio2 at inclusion, the number of days free of respiratory support at 28 days remained not significantly different between groups, with an adjusted mean difference of −3 days (95% CI, −6 to 1; P = .12). For the secondary outcome of endotracheal intubation, the results remained statistically significant, with an adjusted odds ratio for intubation for the helmet group of 0.27 (95% CI, 0.10-0.70; P = .02).

Discussion

In this randomized, multicenter, open-label clinical trial conducted in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation did not result in significantly fewer days of respiratory support at 28 days from randomization as compared with high-flow nasal oxygen alone.

Among 9 prespecified secondary outcomes, 7 showed no significant differences between groups. Treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation was associated with a significantly lower rate of endotracheal intubation and increased invasive ventilation–free days on a 28-day basis. During treatments, patients receiving helmet noninvasive ventilation showed improved oxygenation and dyspnea, while device-related discomfort and Paco2 were lower in patients undergoing high-flow nasal oxygen.

Face-mask noninvasive ventilation has been proposed for the management of hypoxemic respiratory failure, with conflicting results.4,20,25-31 Thus, recent guidelines have been unable to provide conclusive recommendations on the use of face-mask noninvasive ventilation in patients with hypoxemia,1 while the use of high-flow nasal oxygen was encouraged.8

Helmet noninvasive ventilation has been advocated as an alternative for the noninvasive support of patients with hypoxemia.10,12 Use of the helmet interface allows delivery of high positive end-expiratory pressure levels for prolonged treatments with good tolerability, which improves oxygenation and may prevent the occurrence of lung injury when spontaneous breathing is maintained.13,14,32 In spontaneously breathing patients with hypoxemia, high positive end-expiratory pressure increases functional residual capacity and reduces inspiratory effort, tidal volume, and ventilatory inhomogeneity.13 This may aid successful management of patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, in whom treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation has been proven to improve oxygenation and reduce inspiratory effort as compared with high-flow nasal oxygen.15 Inspiratory effort relief and improvement of hypoxemia are associated with avoidance of intubation during noninvasive support.15,33-35

In previous randomized trials, both helmet noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula have been shown to reduce intubation rate and improve survival in patients with most severe hypoxemia compared with noninvasive ventilation sessions delivered through face mask.10,19 To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial comparing helmet noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal oxygen in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure.

In this study, treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation did not result in a reduced duration of respiratory support, but was associated with improved oxygenation and dyspnea, reduced rate of endotracheal intubation, and increased days free of invasive ventilation at 28 days from randomization. These results indicate that noninvasive respiratory support with helmet noninvasive ventilation did not directly affect the disease process and the duration of the need for respiratory support, but enabled successful noninvasive management with avoidance of intubation in a greater proportion of patients.

The rate of endotracheal intubation during high-flow nasal oxygen in the cohort was close to that reported by other investigators in patients with severe COVID-19.36,37 The results largely confirmed the data of a recent systematic meta-analysis on acute hypoxemic respiratory failure from heterogeneous causes that suggested a reduction in the intubation rate with helmet noninvasive ventilation when compared with high-flow nasal oxygen.11 Avoidance of intubation appears of paramount importance to prevent the complications related to invasive mechanical ventilation, sedation, delirium, and paralysis.38,39 Also, successful management of patients with hypoxemia without endotracheal intubation allows more efficient resource allocation in the intensive care unit, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.6 High-flow nasal oxygen is recommended as first-line intervention for patients with hypoxemia8: the data from this trial indicate that an early trial with helmet noninvasive ventilation may possibly benefit patients with most severe oxygenation impairment.

Importantly, in this study, strict monitoring of patients and well-specified criteria for defining treatment failure were used, possibly limiting the occurrence of delays in the decision to intubate the patients. Monitoring of patients receiving noninvasive support during acute hypoxemic respiratory failure remains of paramount importance not to delay endotracheal intubation and protective ventilation.9

The study has several strengths: the randomized multicenter design with reproducible enrollment criteria, well-defined treatment protocols that can be applied in other intensive care units, strict prespecified criteria for defining the need for endotracheal intubation, and a process of external validation by 3 independent experts to verify the adherence to such criteria for intubated patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the limited sample could have made the study underpowered to detect small differences between groups in the primary end point. Second, helmet noninvasive ventilation has been applied continuously for at least 48 hours with high positive end-expiratory pressure and relatively low pressure support in centers with expertise with this technique. Use of this technique with different ventilator settings, with nonadequate personnel expertise, and/or in intermittent sessions may not provide the same benefits observed in our study. Third, the use of awake prone positioning was not standardized and occurred more frequently in patients in the high-flow nasal oxygen group, as per clinical decision: this does not alter, and could even strengthen, the significance of the results on endotracheal intubation because prone positioning could have optimized the perceived benefit by high-flow oxygen.18 Fourth, all enrolled patients were affected by COVID-19, and the results, despite being physiologically sound and consistent with the most recent literature on acute hypoxemic respiratory of other ethiologies,11 may not fully be generalizable to hypoxemic respiratory failure due to other causes.18

Conclusions

Among patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemia, treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation, compared with high-flow nasal oxygen, resulted in no significant difference in the number of days free of respiratory support within 28 days. Further research is warranted to determine effects on other outcomes, including the need for endotracheal intubation.

Section Editor: Christopher Seymour, MD, Associate Editor, JAMA (christopher.seymour@jamanetwork.org).

Article Information

Corresponding Author: Domenico L. Grieco, MD, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Lgo F Vito, 00168, Rome, Italy (dlgrieco@outlook.it).

Accepted for Publication: March 12, 2021.

Published Online: March 25, 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4682

Author Contributions: Drs Grieco and Menga had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Grieco, Pintaudi, Dell'Anna, Bocci, De Pascale, Volta, Conti, Maggiore, Antonelli.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Grieco, Menga, Cesarano, Rosà, Spadaro, Bitondo, Montomoli, Falò, Tonetti, Cutuli, Pintaudi, Tanzarella, Piervincenzi, Bongiovanni, Dell’Anna, Delle Cese, Berardi, Carelli, Montini, Bello, Natalini, De Pascale, Velardo, Volta, Ranieri, Antonelli.

Drafting of the manuscript: Grieco, Menga, Cesarano, Pintaudi, Bongiovanni, Dell’Anna, Carelli, Bocci, Natalini, De Pascale, Antonelli.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Grieco, Menga, Rosà, Spadaro, Bitondo, Montomoli, Falò, Tonetti, Cutuli, Pintaudi, Tanzarella, Piervincenzi, Bongiovanni, Delle Cese, Berardi, Montini, Bello, De Pascale, Velardo, Volta, Ranieri, Conti, Maggiore, Antonelli.

Statistical analysis: Grieco, Montini, De Pascale, Velardo.

Obtained funding: Grieco, Antonelli.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Grieco, Cesarano, Rosà, Spadaro, Bitondo, Pintaudi, Tanzarella, Piervincenzi, Bongiovanni, Dell’Anna, Bocci, Natalini, De Pascale, Antonelli.

Supervision: Grieco, Spadaro, Pintaudi, Piervincenzi, Bongiovanni, Dell’Anna, Bocci, Bello, De Pascale, Volta, Ranieri, Conti, Maggiore, Antonelli.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Grieco reported receiving grants from the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care Medicine during the conduct of the study and grants from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and GE Healthcare and travel expenses from Maquet, Getinge, and Air Liquide outside the submitted work. Dr Montomoli reported receiving personal fees from Active Medica BV outside the submitted work. Dr Conti reported receiving payments for lectures from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals SpA. Dr Maggiore reported serving as the principal investigator of the RINO trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02107183), which was supported by Fisher and Paykel Healthcare through an institutional grant, and receiving personal fees from Draeger Medical and GE Healthcare outside the submitted work. Dr Antonelli reported receiving personal fees from Maquet, Chiesi, and Air Liquide and grants from GE Healthcare outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: The study was funded by a research grant (2017 Merck Sharp & Dohme SRL award) by the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care Medicine.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Group Information: The COVID-ICU Gemelli Study Group members are listed in Supplement 4.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 5.

Additional Contributions: We are grateful to all intensive care unit physicians, residents, nurses, and personnel from the participating centers, whose sacrifice, efforts, devotion to patients, and passion have made possible this timely report. We are grateful to Jean-Pierre Frat, MD, PhD (Poitiers, France), Oriol Roca, MD, PhD (Barcelona, Spain), and Jordi Mancebo, MD, PhD (Barcelona, Spain), for their contribution as members of the adjudication committee for endotracheal intubation. We are grateful to Cristina Cacciagrano, Emiliano Tizi, and Alberto Noto, MD, for their contribution to study organization. We are grateful to Gabriele Esposito, PD, for Figure 1 drafting. Drs Frat, Roca, and Velardo received a personal fee for their contribution to the study; all others listed did not receive compensation.

Additional Information: The study was endorsed by the Insufficienza Respiratoria Acuta e Assistenza Respiratoria study group of the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care Medicine.

References

1.Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1602426. doi:10.1183/13993003.02426-2016PubMedGoogle Scholar

2.Yoshida T, Fujino Y, Amato MBP, Kavanagh BP. Fifty years of research in ARDS: spontaneous breathing during mechanical ventilation: risks, mechanisms, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(8):985-992. doi:10.1164/rccm.201604-0748CPPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

3.Grieco DL, Menga LS, Eleuteri D, Antonelli M. Patient self-inflicted lung injury: implications for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and ARDS patients on non-invasive support. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85(9):1014-1023. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13418-9PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

4.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Noninvasive ventilation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: insights from the LUNG SAFE Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(1):67-77. doi:10.1164/rccm.201606-1306OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

5.Franco C, Facciolongo N, Tonelli R, et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of out-of-ICU noninvasive respiratory support in patients with COVID-19-related pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(5):2002130. doi:10.1183/13993003.02130-2020PubMedGoogle Scholar

6.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5394

ArticlePubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

7.COVID-ICU Group on behalf of the REVA Network and the COVID-ICU Investigators. Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(1):60-73. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06294-xPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

8.Rochwerg B, Einav S, Chaudhuri D, et al. The role for high flow nasal cannula as a respiratory support strategy in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(12):2226-2237. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06312-yPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

9.Mellado-Artigas R, Ferreyro BL, Angriman F, et al; COVID-19 Spanish ICU Network. High-flow nasal oxygen in patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory failure. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):58. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03469-wPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

10.Patel BK, Wolfe KS, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Effect of noninvasive ventilation delivered by helmet vs face mask on the rate of endotracheal intubation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2435-2441. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6338

ArticlePubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

11.Ferreyro BL, Angriman F, Munshi L, et al. Association of noninvasive oxygenation strategies with all-cause mortality in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(1):57-67. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9524

ArticlePubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

12.Antonelli M, Conti G, Pelosi P, et al. New treatment of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: noninvasive pressure support ventilation delivered by helmet: a pilot controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(3):602-608. doi:10.1097/00003246-200203000-00019PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

13.Morais CCA, Koyama Y, Yoshida T, et al. High positive end-expiratory pressure renders spontaneous effort noninjurious. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1285-1296. doi:10.1164/rccm.201706-1244OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

14.Yoshida T, Grieco DL, Brochard L, Fujino Y. Patient self-inflicted lung injury and positive end-expiratory pressure for safe spontaneous breathing. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26(1):59-65. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000691PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

15.Grieco DL, Menga LS, Raggi V, et al. Physiological comparison of high-flow nasal cannula and helmet noninvasive ventilation in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(3):303-312. doi:10.1164/rccm.201904-0841OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

16.Grieco DL, Toni F, Santantonio MT, et al. Comfort during high-flow oxygen therapy through nasal cannula in critically ill patients: effects of gas temperature and flow. Presented at the 26th Annual Congress of the European Society of Intensive Medicine; October 5-9, 2013; Paris, France.

17.Muriel A, Peñuelas O, Frutos-Vivar F, et al. Impact of sedation and analgesia during noninvasive positive pressure ventilation on outcome: a marginal structural model causal analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(9):1586-1600. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-3854-6PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

18.Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):765-774. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30268-XPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

19.Frat J-P, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al; FLORALI Study Group; REVA Network. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2185-2196. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503326PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

20.Antonelli M, Conti G, Rocco M, et al. A comparison of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(7):429-435. doi:10.1056/NEJM199808133390703PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

21.Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and Society of Critical Care Medicine. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1253-1263. doi:10.1164/rccm.201703-0548STPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

22.Boles J-M, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(5):1033-1056. doi:10.1183/09031936.00010206PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

23.Maggiore SM, Idone FA, Vaschetto R, et al. Nasal high-flow versus Venturi mask oxygen therapy after extubation: effects on oxygenation, comfort, and clinical outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):282-288. doi:10.1164/rccm.201402-0364OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

24.Menga LS, Cese LD, Bongiovanni F, et al. High failure rate of noninvasive oxygenation strategies in critically ill subjects with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19. Respir Care. 2021;(March):respcare.08622. doi:10.4187/respcare.08622PubMedGoogle Scholar

25.Carrillo A, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Ferrer M, et al. Non-invasive ventilation in community-acquired pneumonia and severe acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(3):458-466. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2475-6PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

26.Hilbert G, Gruson D, Vargas F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(7):481-487. doi:10.1056/NEJM200102153440703PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

27.Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Leon M, Gonzalez G, Alarcon A, Torres A. Noninvasive ventilation in severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(12):1438-1444. doi:10.1164/rccm.200301-072OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

28.Demoule A, Chevret S, Carlucci A, et al; oVNI Study Group; REVA Network (Research Network in Mechanical Ventilation). Changing use of noninvasive ventilation in critically ill patients: trends over 15 years in francophone countries. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(1):82-92. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-4087-4PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

29.Demoule A, Girou E, Richard J-C, Taille S, Brochard L. Benefits and risks of success or failure of noninvasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1756-1765. doi:10.1007/s00134-006-0324-1PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

30.Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Arancibia F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation during persistent weaning failure: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):70-76. doi:10.1164/rccm.200209-1074OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

31.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(4):438-442. doi:10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CPPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

32.Goligher EC, Dres M, Patel BK, et al. Lung- and diaphragm-protective ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):950-961. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0655CPPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

33.Tonelli R, Fantini R, Tabbì L, et al. Early inspiratory effort assessment by esophageal manometry predicts noninvasive ventilation outcome in de novo respiratory failure: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(4):558-567. doi:10.1164/rccm.201912-2512OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

34.Antonelli M, Conti G, Esquinas A, et al. A multiple-center survey on the use in clinical practice of noninvasive ventilation as a first-line intervention for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):18-25. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000251821.44259.F3PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

35.Carteaux G, Millán-Guilarte T, De Prost N, et al. Failure of noninvasive ventilation for de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: role of tidal volume. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):282-290. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001379PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

36.Demoule A, Vieillard Baron A, Darmon M, et al. High-flow nasal cannula in critically iii patients with severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):1039-1042. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-2007LEPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

37.Zucman N, Mullaert J, Roux D, Roca O, Ricard J-D; Contributors. Prediction of outcome of nasal high flow use during COVID-19–related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(10):1924-1926. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06177-1PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

38.Goligher EC, Fan E, Herridge MS, et al. Evolution of diaphragm thickness during mechanical ventilation: impact of inspiratory effort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(9):1080-1088. doi:10.1164/rccm.201503-0620OCPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

39.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683-693. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022450PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

Source: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2778088?guestAccessKey=7ca7e397-4cac-4fa6-abe5-07919d3affab&utm_source=silverchair&utm_campaign=jama_network&utm_content=covid_weekly_highlights&utm_medium=email

Other library

- One in 10 People Who Had Omicron Got Long COVID: Study ( 20:25 - 01/06/2023 )

- Physical Medicine Academy Issues Guidance on Long COVID Neurologic Symptoms ( 09:58 - 19/05/2023 )

- Breakthrough' Study: Diabetes Drug Helps Prevent Long COVID ( 08:55 - 15/03/2023 )

- BCG vaccine (thuốc chủng ngừa bệnh lao) & SARS-CoV 2 (covid-19) infection ( 10:08 - 27/10/2022 )

- Đại dịch COVID-19 đã kết thúc? ( 09:11 - 22/09/2022 )

- Dị hình giới tính ở COVID-19: Ý nghĩa tiềm năng về lâm sàng và sức khỏe cộng đồng ( 09:22 - 19/03/2022 )

- COVID-19 Update ( 21:00 - 06/03/2022 )

- Một người có thể tái mắc Covid-19 bao nhiêu lần ?? / kèm 6 tài liệu mới ... do "waning immunity", xảy ra ≥6 tháng sau chủng ngừa hay mắc nhiễm .. ( 20:25 - 06/03/2022 )

- T-cells from common colds can provide protection against COVID-19 - study ( 08:25 - 11/01/2022 )

- Coronavirus Can Spread to Heart, Brain Days After Infection ( 07:56 - 30/12/2021 )