Contact Admission

International Collaboration

Scientists Discover How Stress Can Cause Gray Hair

These file photos, Oct. 7, 2009, left, and Nov. 28, 2012, right, show President Barack Obama speaking in Washington. (AP Photo, File)

A new study provides scientific evidence to support the idea that stress can cause a person’s hair to turn gray. A team from America’s Harvard University said the new study is the first to show a clear link between stress and graying hair. The findings were recently published in the journal Nature.

Researchers say they discovered a chemical process that can change hair color during times of stress. The process is linked to the body’s “fight-or-flight” reaction that can happen during dangerous situations.

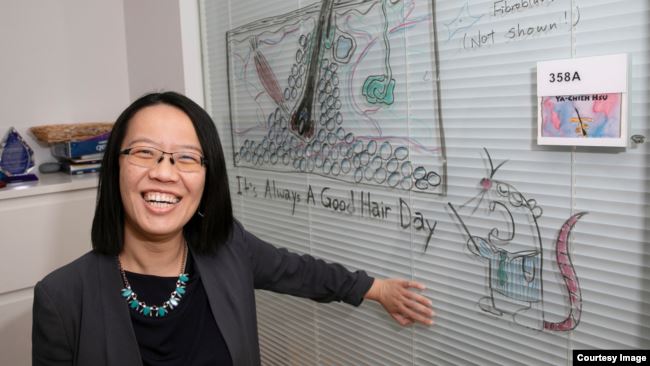

Ya-Chieh Hsu is a professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard. She said in a statement that the research team was in search of the first scientific confirmation of the commonly held belief that stress can cause gray hair. “Everyone has an anecdote to share about how stress affects their body, particularly in their skin and hair - the only tissues we can see from the outside,” Hsu said.

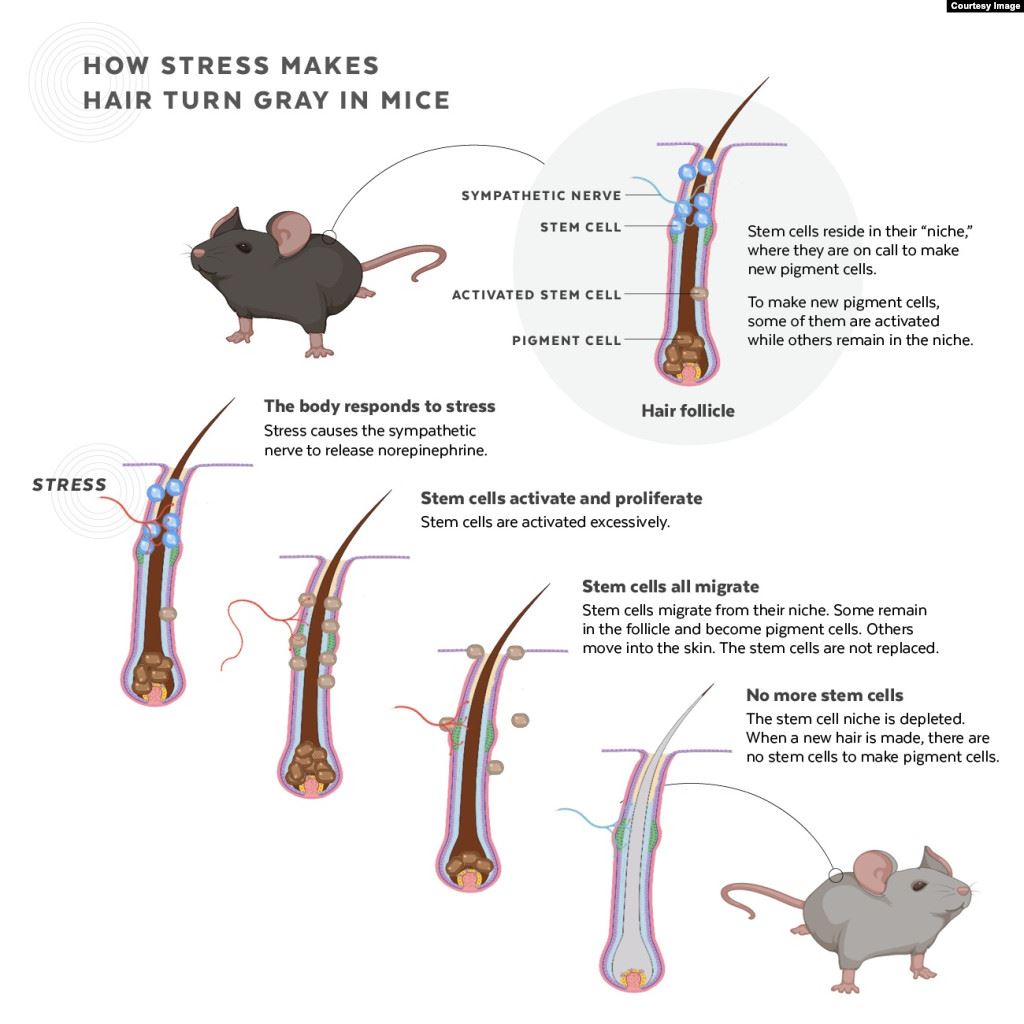

The team used experiments with mice to look at how stress affects stem cells in hair follicles. Most people have about 100,000 hair follicles on their head. The follicles are responsible for making melanocytes, the cells that give hair its color. As people age, melanocyte production is reduced. This causes a person’s hair to begin turning gray naturally.

At first, the researchers suspected that an immune attack caused by a stressful event might be targeting the melanocyte stem cells. That theory, however, turned out to be false. The mice lacking immune cells still showed signs of graying hair.

The team also thought the hormone cortisol, which always increases in the body during times of stress, might be a likely cause. However, when researchers removed the gland that produces the cortisol hormones, the hair of mice still turned gray.

This infographic depicts how stem cells are depleted in response to stress, causing hair to turn gray in mice. (Judy Blomquist/Harvard University)

The scientists then centered their experiments on the body’s sympathetic nervous system. This is the body system that controls “fight-or-flight” reactions in dangerous situations.

The sympathetic nervous system is made up of a collection of nerves that extend through the body, including the skin. When the mice were subjected to short-term pain or placed in stressful laboratory conditions, these nerves released a chemical called norepinephrine. The chemical then flowed through the stem cells up into the hair follicles -- where melanocytes are kept.

The researchers found that when the norepinephrine was released, all the melanocyte stem cells were highly activated and changed into pigment-producing cells. This overproduction process resulted in the early loss of color-producing cells.

Ya-Chieh Hsu said the experiments confirmed the team’s belief that stress is bad for the body. She added that the results demonstrated the harmful effects are more major than what the researchers had imagined. “After just a few days, all of the pigment-regenerating stem cells were lost. Once they’re gone, you can’t regenerate pigments anymore. The damage is permanent,” Hsu said.

Professor Ya-Chieh Hsu, senior author of the study, shows off a diagram of a hair follicle - complete with a helpful test mouse. Ya-Chieh Hsu has received the Rosslyn-Abramson award for teaching. (Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer)

The scientists said their research could lead to new treatments for stress-related graying in the future. Graying hair is just one example of how stress affects the body. New experiments could also be carried out in other areas, as well, the team said. These could include studies to see whether stress can also cause changes in body tissues.

Hsu said she would also like to study whether stress has a large effect on the overall aging process. “We don’t know if that is true yet. We are interested in finding out the link,” she said.

Other news

- How Dangerous Is Nipah Virus? Medical Alert and Urgent Health Recommendations ( 14:13 - 27/01/2026 )

- Predicting Disease from Sleep – A New Breakthrough Study ( 14:01 - 13/01/2026 )

- Medical advances predicted to break through in 2026 ( 13:54 - 12/01/2026 )

- Vietnamese medical miracles in 2025 – inspiration for medical students ( 07:54 - 07/01/2026 )

- Updating the SOFA-2 Score: A New Standard in the Assessment of Multiple Organ Failure After Three Decades ( 10:40 - 31/12/2025 )

- Home AEDs: High Life-Saving Effectiveness, but Not Cost-Effective at Current Prices ( 14:12 - 18/12/2025 )

- Artificial Intelligence and Pediatric Care ( 08:27 - 16/12/2025 )

- Applying Clinical Licensing Principles to Artificial Intelligence ( 09:36 - 08/12/2025 )

- U.S. Approves Targeted Lung Cancer Therapy Datroway ( 08:43 - 25/06/2025 )

- Therapeutic potential and mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as bioactive materials in tendon–bone healing ( 08:38 - 23/11/2023 )